In the realm of accounting, IAS 12 Income Tax is a beacon that guides the recognition and measurement of income tax, including both current and deferred tax. Yet, for many, its intricacies seem akin to navigating a labyrinth. IAS12 Income taxes, deals with the accounting of income taxes (current taxes and deferred tax) rather than the method of computing the amount of tax liability. This blog post aims to demystify IAS 12, turning its complex passages into straightforward paths.

The Core of IAS 12: A Dual Perspective

At its heart, IAS 12 operates on a fundamental premise: income taxes affect a company’s cash flows and its financial position. Therefore, understanding and applying IAS 12 is crucial for accurate financial reporting.

1. Current Tax:

This is the amount you owe to or will receive from the tax authorities for the current year. It’s pretty straightforward — calculate your income, apply the tax rate, and there you have it, your current tax expense or benefit.

2. Taxable Profit (Tax Loss):

This is the net result of the period’s financial activities as recognized by tax laws. If you’ve made more money than you’ve spent, you have a taxable profit. If it’s the other way around, you have a tax loss.

3. Under/Over Provision of Taxes of Previous Year:

Sometimes, you might estimate your taxes and end up paying more or less than what you actually owe. If you paid less, you have an under-provision; if you paid more, it’s an over-provision.

- Under-provision means you didn’t set aside enough money for taxes in the previous year, so you’ll need to recognize an additional tax expense in the current year.

- Over-provision means you set aside too much money for taxes in the previous year, so you’ll get to reduce your current year’s tax expense.

4. Deferred Tax:

Here lies the twist in the tale. Deferred tax arises from temporary differences between the tax base of an asset or liability (what the tax authorities consider its value for tax purposes) and its carrying amount in your financial statements. Simply put, it’s about timing differences — when you recognize income or expenses in your accounts versus when they are taxable or deductible.

Example:

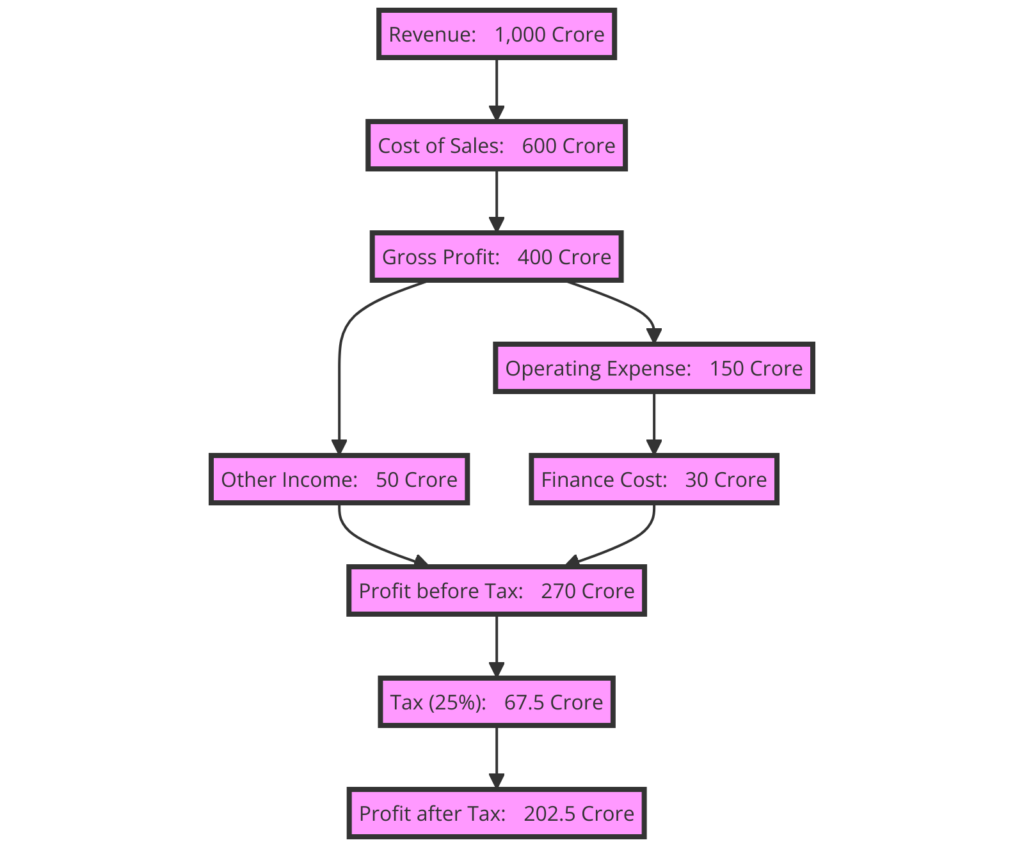

To explain the calculation of income tax as per IAS 12 using a simplified income statement, let’s consider the following hypothetical financials for an electric vehicle manufacturing company, VoltMakers Ltd., for the fiscal year ending:

- Revenue: ₹1,000 Crore

- Cost of Sales: ₹600 Crore

- Gross Profit: ₹400 Crore (Revenue – Cost of Sales)

- Operating Expense: ₹150 Crore

- Other Income: ₹50 Crore

- Finance Cost: ₹30 Crore

- Profit before Tax: ₹270 Crore (Gross Profit – Operating Expense + Other Income – Finance Cost)

- Tax Rate: 25%

Calculating Income Tax as per IAS 12:

IAS 12 Income Taxes requires the use of the balance sheet liability method to account for income taxes, which includes both current tax and deferred tax.

Current Tax: The amount of income taxes payable (or recoverable) in respect of the taxable profit (or tax loss) for the period. For VoltMakers Ltd.:

- Profit Before Tax (PBT): ₹270 Crore

- Tax Rate: 25% Current Tax Expense = PBT x Tax Rate

= ₹270 Crore x 25% = ₹67.5 Crore

Deferred Tax: Arises due to temporary differences between the carrying amount of assets and liabilities for financial reporting purposes and the amounts used for taxation purposes.

postponed or delayed. suspended or withheld for or until a certain time or event: a deferred payment; deferred taxes.

For simplicity, let’s assume there are no temporary differences or unused tax losses leading to deferred tax assets or liabilities for VoltMakers Ltd. in this fiscal year.

Profit After Tax Calculation:

- Profit before Tax: ₹270 Crore

- Tax Expense (Current Tax): ₹67.5 Crore

Profit After Tax (PAT) = Profit Before Tax – Tax Expense

= ₹270 Crore – ₹67.5 Crore = ₹202.5 Crore

Bridging the Temporary Differences

Imagine you have an asset that you depreciate faster for tax purposes than in your financial statements. Initially, you’ll pay less tax (a temporary tax saving), but as the asset’s book value catches up with its tax base, you’ll end up paying more tax in the future. Deferred tax accounts for these future tax payments or savings today, ensuring that your financial statements reflect future tax implications of your current transactions. Temporary differences are differences between the carrying amount of an asset or liability in the statement of financial position and its tax base.

Temporary Difference = Carrying Value – Tax base Value

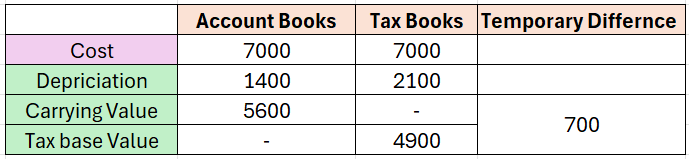

Let’s assume VoltMakers Ltd. purchased a piece of equipment for use in their electric vehicle manufacturing process. For simplicity, let’s say the cost is ₹7000.

In the Accounting Books:

- The asset is depreciated by ₹1400 each year for 5 years (straight-line depreciation).

- After the first year, the carrying value is ₹5600 (₹7000 – ₹1400).

In the Tax Books:

- For tax purposes, the asset is depreciated at a different rate, say ₹2100 per year.

- After the first year, the tax base, which is the carrying amount for tax purposes, is ₹4900 (₹7000 – ₹2100).

Now, for the temporary difference:

- At the end of year one, we have a carrying value in the accounting books of ₹5600 and a tax base of ₹4900 From Tax Books

- The temporary difference is ₹700 (₹5600 – ₹4900).

The existence of this ₹700 temporary difference will lead to deferred tax consequences. If the tax rate is 30%, the deferred tax liability created is 30% of ₹700, which is ₹210.

VoltMakers Ltd. will need to recognize this deferred tax liability in their financial statements because, in the future, they will pay less tax when this temporary difference reverses (i.e., when the asset is fully depreciated in the tax books but still has a carrying value in the accounting books).

In subsequent years, as the asset continues to be depreciated, this temporary difference will change, and the deferred tax liability will be adjusted accordingly. Once the asset is fully depreciated in both sets of books, the temporary difference will be zero, and the deferred tax liability related to this asset will be fully reversed.

Recognizing Deferred Tax: The Balancing Act

IAS 12 requires entities to recognize deferred tax liabilities for all taxable temporary differences and deferred tax assets for all deductible temporary differences, to the extent that it’s probable that taxable profit will be available against which the temporary difference can be utilized.

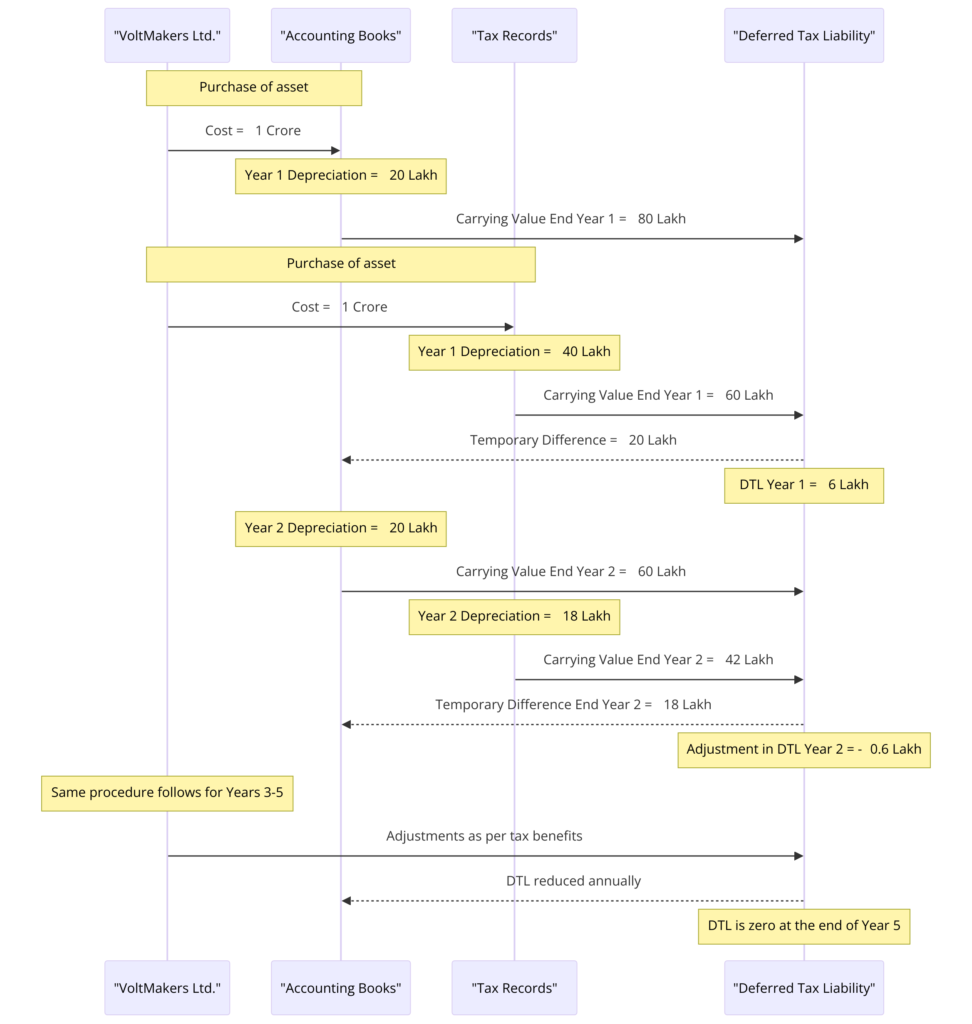

Certainly! Let’s consider a simplified example for an electric vehicle company called VoltMakers Ltd.

VoltMakers Ltd. has invested in a new battery technology system for their electric vehicles. The cost of the system is ₹1 Crore, and it will be used over a span of 5 years. According to their accounting practices, they will depreciate the system on a straight-line basis, which means an annual depreciation of ₹20 Lakh in their books. However, for tax purposes, the government allows an accelerated depreciation of 40% for the first year and 30% for the second year on the reducing balance, which is intended to promote investment in new technology. The remaining balance will be depreciated equally over the next three years.

Assuming a tax rate of 30%, let’s calculate the deferred tax.

Year 1:

- Accounting Depreciation: ₹1 Crore / 5 years = ₹20 Lakh

- Tax Depreciation: 40% of ₹1 Crore = ₹40 Lakh

- Temporary Difference: ₹40 Lakh (Tax) – ₹20 Lakh (Accounting) = ₹20 Lakh

- Deferred Tax Liability (DTL) Year 1: 30% of ₹20 Lakh = ₹6 Lakh

Journal Entry for Year 1:

- Debit Income Tax Expense (Profit & Loss): ₹6 Lakh

- Credit Deferred Tax Liability (Balance Sheet): ₹6 Lakh

Year 2:

- New Book Value (after accounting for Year 1 depreciation): ₹1 Crore – ₹20 Lakh = ₹80 Lakh

- New Tax Base (after accounting for Year 1 tax depreciation): ₹1 Crore – ₹40 Lakh = ₹60 Lakh

- Tax Depreciation Year 2: 30% of ₹60 Lakh = ₹18 Lakh

- Accounting Depreciation Year 2: ₹20 Lakh

- Temporary Difference: ₹18 Lakh (Tax) – ₹20 Lakh (Accounting) = -₹2 Lakh (reversal of temporary difference)

- Change in DTL Year 2: 30% of -₹2 Lakh = -₹0.6 Lakh (reversal of DTL due to lower tax depreciation)

Journal Entry for Year 2:

- Debit Deferred Tax Liability (Balance Sheet): ₹0.6 Lakh

- Credit Income Tax Expense (Profit & Loss): ₹0.6 Lakh

For Years 3-5, similar calculations would be made based on the reducing tax base and the constant accounting depreciation. Eventually, by the end of Year 5, the temporary differences would be zero, meaning the cumulative tax depreciation will equal the cumulative accounting depreciation, and the Deferred Tax Liability related to this asset will be zero.

This method of recognizing deferred tax ensures that the tax expenses presented in the income statement each year are matched with the corresponding accounting profits, aligning with the accrual accounting principle. An engineer can appreciate that this is akin to the way engineering systems are designed to account for differences in operation over time, ensuring balance and consistency.

Deferred tax in Other Comprehensive Income (OCI)

Deferred tax in Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) arises when there are temporary differences related to items recognized directly in equity, particularly through OCI, rather than through profit or loss. Here’s an example to illustrate the impact of deferred tax on OCI:

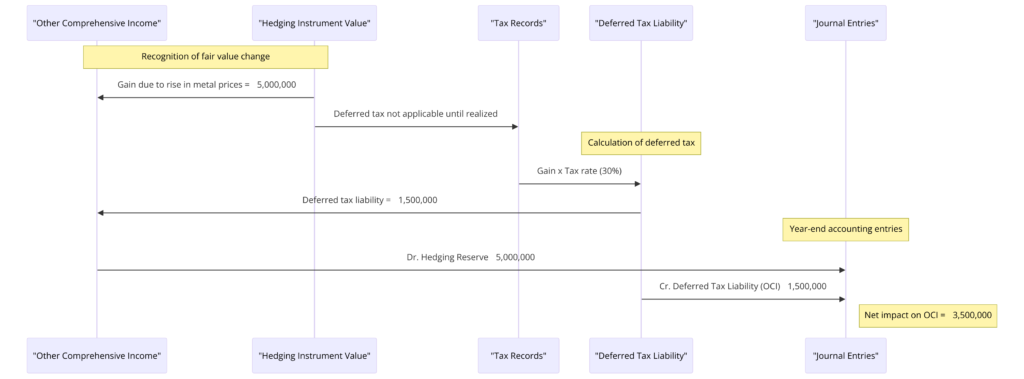

Example – Hedging Instrument Impact in OCI:

Let’s assume VoltMakers Ltd. has entered into a hedging contract to protect against fluctuations in metal prices, which are a significant part of their electric vehicle (EV) battery production costs. According to accounting standards, the fair value changes of the hedging instrument are recognized in OCI until the forecast transaction affects the profit or loss.

At the end of the year, the fair value of the hedging instrument has increased by ₹5,000,000, reflecting a gain due to the rise in metal prices. This gain is not taxable until realized; therefore, it creates a temporary difference.

Here is how the deferred tax would be accounted for:

- In the Statement of Comprehensive Income:

- The gain on the hedging instrument is recognized in OCI: ₹5,000,000.

- Deferred Tax Impact in OCI:

- Assuming a tax rate of 30%, the deferred tax on this would be ₹5,000,000 * 30% = ₹1,500,000.

- This deferred tax amount is also recognized in OCI but as a deferred tax liability because it represents taxes that will be paid in the future when the hedging gain is realized.

- Journal Entries for the Year-end Accounting:

- OCI (Gain on Hedging Instrument):

Dr. Hedging Reserve ₹5,000,000 - Deferred Tax Liability:

Cr. Deferred Tax Liability (OCI) ₹1,500,000

In this example, the company’s total comprehensive income is impacted by the gain on the hedge and the associated deferred tax liability. While the hedge gain increases OCI, the deferred tax liability reduces it. The net amount reported in OCI for the year would be the hedge gain minus the deferred tax impact, which in this case is ₹5,000,000 – ₹1,500,000 = ₹3,500,000.

Remember, the deferred tax liability will be settled once the hedging gain impacts the profit or loss when the forecast transaction occurs (e.g., when the metals are actually purchased at the locked-in prices), at which point the deferred tax will reverse and affect the tax expense in the income statement.

The Impact of IAS 12 on Financial Statements

Understanding and applying IAS 12 can significantly impact an entity’s financial statements. Deferred taxes are not merely numbers on a balance sheet; they symbolize future cash flows affected by today’s transactions and events. They are an essential consideration for investors, creditors, and other stakeholders in assessing an entity’s financial health.

Applying IAS 12 involves significant judgement, particularly in estimating the amount of taxable profits available for the utilization of deductible temporary differences. It requires a forward-looking approach, considering future changes in laws, tax rates, and business strategies.

Conclusion: Simplified, Not Simplistic

While IAS 12 might seem daunting with its deferred tax calculations and judgements, its essence is to ensure that the financial statements present a complete picture of an entity’s tax-related inflows and outflows. It’s about matching the tax effects of transactions with their accounting implications.

IAS 12 demystified is less about navigating a labyrinth and more about understanding a map that guides you through the tax implications of your business activities. By recognizing both current and deferred taxes, entities ensure that their financial statements accurately reflect their financial position and performance, providing transparency and insight to stakeholders. In this journey, the complexity of IAS 12 becomes a tool for clarity, helping entities like EcoVolt Motors illuminate their financial paths with the foresight of tax planning and compliance.